Dependencyphobia

In case the title is not obvious, dependencies drive me crazy! They do speed up development in many cases, but they introduce a lot of complications in the process. So, in this overthinking article, I will rant about my fear of dependencies. I do use them, of course, as we all do. But I still avoid them whenever I can, and you’ll see why. There will be some practical advice at the end.

My History with Dependencies

Like most beginner data scientists, I learned R with tutorials and courses that heavily use the Tidyverse. Tidyverse is to R a bit like frameworks are to JS: a collection of packages that let you write code in an organized and opinionated way. After learning more about both Tidy packages and base R (i.e., the standard library), I began to realize that the Tidyverse evolved to be like a whole dialect of R. In many places, it resists the standard behavior by adding new data structures and new ways to write code, which is non-idiomatic as far as base R is concerned… Not that I cared at the time.

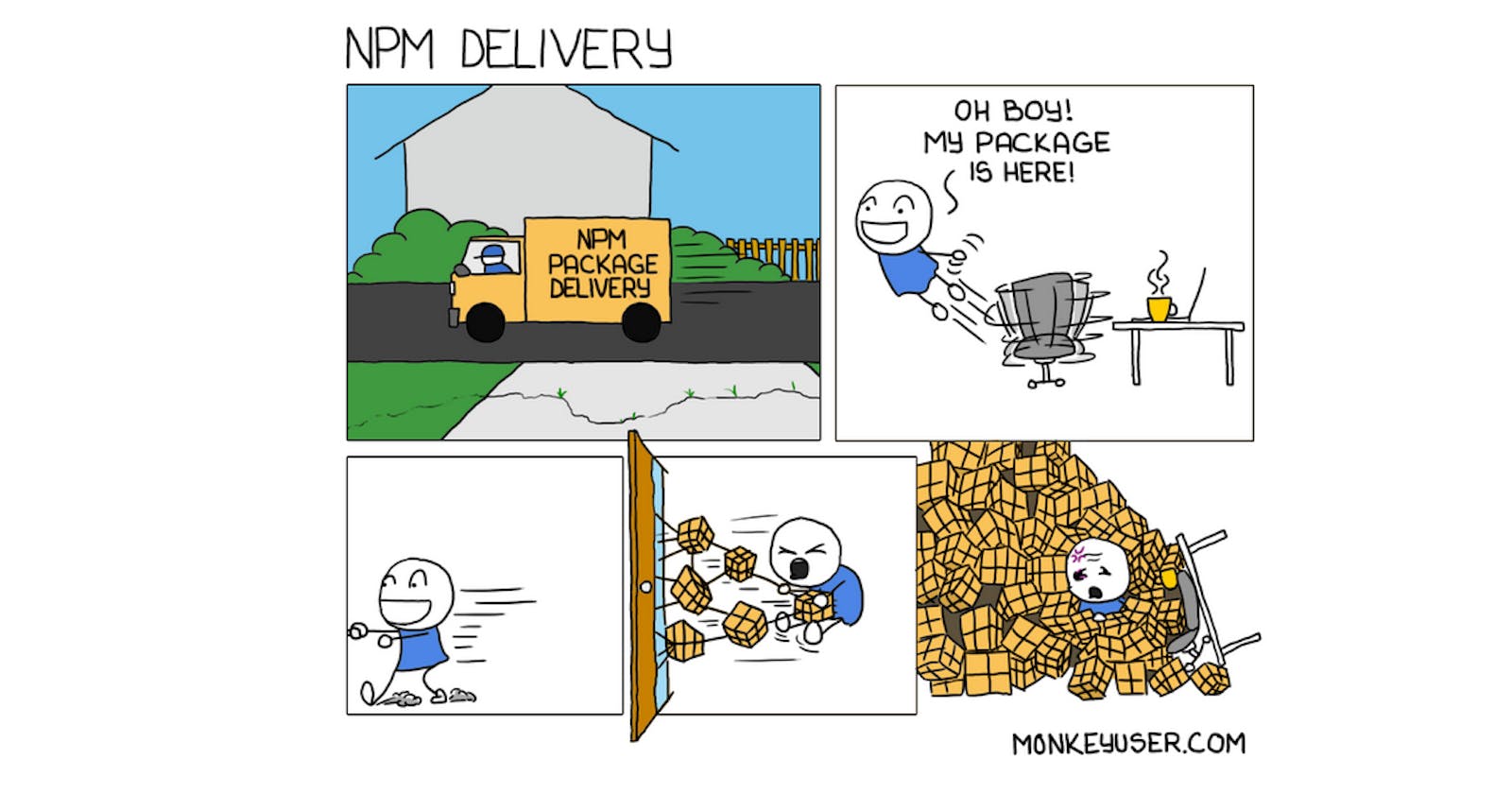

I got into the habit of downloading packages for anything I want to do. After all, there is a package for any data task in R, almost like NPM. Then, I began to realize that many of the packages that depend on the Tidyverse (but aren’t developed by the core team) were crashing too often. They gave cryptic errors that are thrown by any of the numerous layers of abstraction between the package and R. Tidyverse packages themselves update way too quickly, and code that is a year (or less) old will throw deprecated warnings when the packages are updated.

(If you are in the web world and find the phrase “packages are updated” a bit strange, we install everything globally in R. Environments and lockfile systems are relatively new and not yet mature. I had many unfortunate issues with them.)

The result is that I started sympathizing with the grumpy old-schoolers that complain about this new dialect that causes all sorts of problems just to make the syntax easier and more SQL-like. I do use the packages but to a minimal degree if I could. I write functions to operate on data. It may not be the most elegant R code one could write, but at least I can debug it.

That’s my story of developing dependencyphobia, and it’s still with me when I code in languages other than R like Python (where they pip install anything) and JavaScript (where they npm install anything). In the next couple of sections, I will discuss the problems with dependencies in some detail.

Bugs

Open source is so Wild West right now. There is always a chance that two pieces of code from separate libraries aren’t compatible with each other. The more libraries you use, the higher the chance things will break. I know it’s not as linear of an association as I put it, and things are a bit more nuanced than that. Different libraries can be trusted more easily than others depending on popularity, active maintenance, corporate backing, etc.

I once heard something that resonated with me. It was along the lines of “if you write less code, you reduce the surface area in which bugs might happen.” Take a moment to think about the fact that installing a library means adding a boatload of code to your project. You don’t see it, but it’s definitely there!

This ties in with the fact that highly abstract packages are usually hard to debug because they operate far from the base language. When an error comes up at a place with a long chain of dependencies, the source of error might be somewhere in the middle of that chain, and that’s a library you didn’t even load or use directly. As far as I know, such bugs have a high probability of being unfixable by you as an end-user of the library. You’d have to open an issue for the author or fix the source yourself.

Non-Transferable Code

It is the practical purpose of a library or a framework to give you some form of abstraction to work with. But a high level of abstraction means a great divergence from idiomatic language code that uses standard library features. As a result, your opinionated code can’t be directly transferred to the base language or another framework with different layers of abstraction. Is this a bad thing? I think being distant from the base language is bad, but I’ll admit it’s a subjective thing. After all, there can’t be a precise standard on what’s “idiomatic” and what’s not.

But it goes far beyond code style. When you write a lot of code and have great experience in a certain framework, that makes you good only at that framework and not at the language as a whole. Unless you actively seek knowledge in the base language and other language-agnostic concepts, you’re left with non-transferable knowledge. That won’t be a problem as long as you stay forever in that walled garden.

Deprecation

This is an issue inherent in open-source software in general. But again, the issue becomes more dangerous with more dependencies. Community packages that are actively maintained get updated way faster than the languages themselves. Also, language maintainers care about backward compatibility more than library maintainers. For these reasons, code written without dependencies is much less prone to deprecation.

The more extreme scenario is a breaking change. That is just sad and gives developers a considerable amount of pain when it happens. The less extreme scenario is that the new update is backward compatible in a technical sense but makes the old version obsolete in a stylistic sense. Think of how React shifted from class-based components to functions. This might be a little problematic or at least confusing if you don’t know about it.

How to Deal with Dependencies

This is the part where I get to be a bit less ranty and more practical, I hope. Here are a couple of ways to mitigate the issues of dependencies.

-

Write more code on your own: I’m sure you saw that coming. There won’t be dependency issues if there are no dependencies in the first place! You could just write a couple of functions that use the base language features if it’s not too complicated to do so. I’d say a slight speed loss is well worth the gain in future-proofing and maintainability of your code.

-

Understand the tradeoffs of opinionated libraries: these are constricting by design, and that can be good at times or bad at others. Make sure you understand how much abstraction you’re about to work with. I don’t want to strongly recommend packages on the unopinionated side. Again, it’s a tradeoff, and the decision depends on the application and developer preference.

-

Vet the libraries you intend to use: there is no way around using a library/framework sometimes, but I advise you to do some assessment and not just install anything you lay your eyes on. You can check a library’s repo and look at the README, stars, last commit date, etc. These things are not direct indicators of quality, but they give you a gauge at least.

-

Study the language more: don’t be just a consumer. If you’re new to this, you might be tempted to install packages for everything because they make your life easier. But I’d argue that it will only be easier when you know what happens under the hood so that you can know where to look and debug in case something breaks. I recall The Primeagen once pointed out that you should aspire not to be a “React Developer” but rather a “JavaScript Developer” that specializes in React.

That’s it! Hope this was useful to you. Feel free to let me know what you think, and thanks for reading!

Cover image source: https://www.monkeyuser.com/2017/npm-delivery/