Clojure as a Lisp

This is the first of hopefully many articles where I write down what I learn about Clojure but in a form where I compare it JavaScript. I like learning that way, and blog articles will help me better digest what I learn and also share it with the world.

So, the first obvious difference between Clojure and JavaScript (and other popular languages for that matter) is that Clojure is a dialect of Lisp. I will discuss what that means, and how I think of it. Note that this discussion is exclusively about syntax. Other differences would be the content of future articles.

Warning: this article (and other articles in this series) are mere observations based on my learning journey. As a beginner, the info I share here may contain some inaccuracies. If you find any, do let me know, and if you are getting started like me, I encourage you to do your own research.

A Brief on Lisp

Lisp is short for List Processing. As the name implies, the language is centered around lists: all language “forms” look like lists (they probably are lists but I don’t know much about that yet). A form could be a data structure, an operation, a function call, or other special forms for conditionals, variable bindings, etc.

An expression with variable binding and arithmetic operations like this in JS

let x = 1 + 2 / 3; // 1 + (2 / 3)

would look like this in Clojure

(def x (+ 1 (/ 2 3)))

This is known as prefix notation as opposed to the infix notation that we are used to in JS and math. As another example, let’s look at a function definition. So this

function abs(x) {

if (x >= 0) {

return x;

} else {

return -x;

}

}

would translate to

(defn abs

[x]

(if (>= x 0)

x

(- x)))

Finally, here’s a little piece of code that was written near the end of chapter 3 in Clojure for the Brave and True.

(defn symmetrize-body-parts

"Expects a seq of maps that have a :name and :size"

[asym-body-parts]

(loop [remaining-asym-parts asym-body-parts

final-body-parts []]

(if (empty? remaining-asym-parts)

final-body-parts

(let [[part & remaining] remaining-asym-parts]

(recur remaining

(into final-body-parts

(set [part (matching-part part)])))))))

The Cons

It seems obvious in the last example that the parentheses increase greatly with the slightest complexity. Some people find that syntax a little jarring to look at. I agree that this may seem difficult to work with. But anything that’s difficult at first becomes a little easier with time until it becomes second nature.

I won’t argue much about conciseness because it could be case-dependent, and I haven’t played too much with Clojure. But here’s the perspective I have so far… On one hand, Lisp languages would be more verbose in cases where the other languages have some neat trick. For example, the JS function definition above could be a simple one-liner with an arrow function and a ternary operator. On the other hand, from what I’ve seen, Clojure has a rich standard library. So, you can just call a function in Clojure that you would have written yourself in JS (or npm installed a package).

The Pros

Now for the pros. What is good in a syntax like this? What’s worth learning a new way of writing and reading code? Right now, I can think of three things.

One is simplicity: once you learn the basics and do some function calls and special forms like if, there is not much else to learn in terms of syntax. It also gives you a uniform way of thinking and learning. Everything looks like (fn args). Every documentation entry states what fn is and what args (if any) are expected to be. Every function name that has a question mark is a predicate that returns a boolean, e.g., (even? 2).

The second is unambiguity: you know exactly what goes into what and in which order. There is very little magic in the syntax, no PEMDAS, no ternaries, no nullish coalescing. It makes the syntax extremely boring but predictable. Combine that with pure functions (it’s a functional language after all), and that should make the code very easy to understand.

The third is flexibility: that syntax is surprisingly less constraining than using statements and keywords. For example, (+) can be called with one argument to be returned as-is, or with no argument to return 0. The same goes for multiplication, but the return value with no arguments is 1. I guess this ties to recursion because there must be a “base case” defined in recursive functions. In JS and other languages with infix notation, that kind of syntax is simply illegal.

What I Think of Lisp

To be completely honest with you and myself, I love it, but I’m in what they call the honeymoon period. I was happy with the discovery of Lisp when I tried Emacs (elisp) a couple of years ago. Now, I am revisiting Lisp in the form of Clojure this time, and I will try using it for actual web development after I’ve learned a bit more about Clojure and the functional programming philosophy. Only time will tell if it pans out for me.

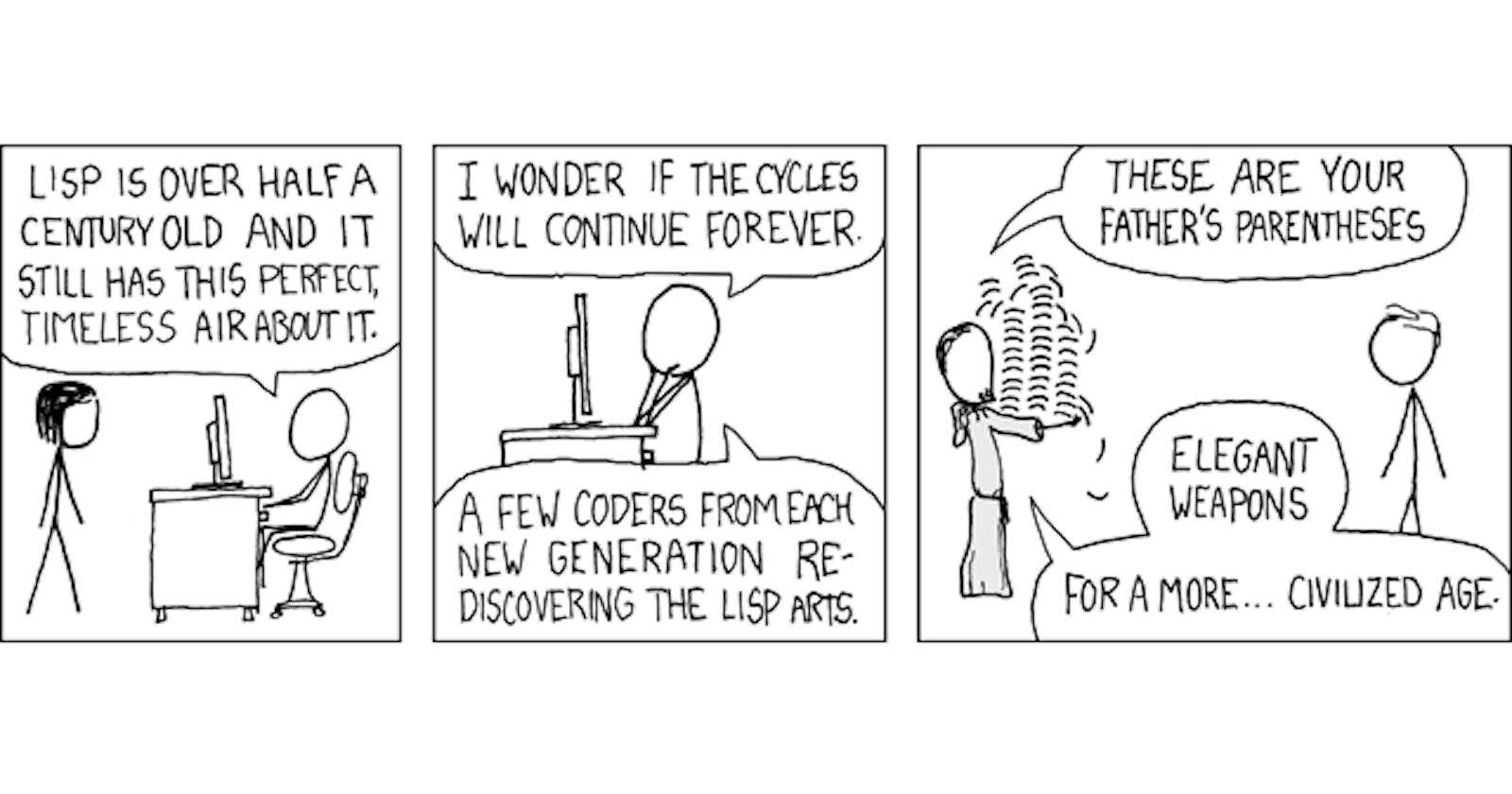

Cover photo by XKCD: https://xkcd.com/297/